“Lay down your arms, ye damned rebels, lay down your arms!”

With that terse warning from Major Pitcairn of the British Army, his guard of

150 soldiers confronted the 77 assembled Minute Men on the town green at

Lexington, Massachusetts. The militia on the Lexington Green on April 19, 1775 had

responded to the alarms spread by Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Dr. Samuel

Prescott. At the time, no one cried “the British are Coming!” Most colonials

still considered themselves British. The cry that did ring out through the New

England countryside that night was “The Regulars are Coming!”

|

| Lexington Green (Photo by Hunner) |

At the Lexington Green, a shot rang out, and the militia

scattered, some run down by the Regulars who charged with bayonets, killing

eight and wounding ten. The Regulars suffered no casualties. Pitcairn marshaled

his jubilant troops back to command and rushed his men to Concord to capture a

stockpile of rebel arms and ammunition.

|

| Reenactors portraying British Regulars at Concord (From exhibit at Minute Man NHP) |

The fighting at Lexington and Concord that April in 1775 sparked

the American Revolutionary War and changed the world. The road to rebellion was

slow boil for the colonists in British America that dated back to the French

and Indian War. Administering the American colonies burdened the growing

British world empire, and Parliament thought payment was due. Beginning in 1733

with the Molasses Act, taxes on essential colonial products raised the ire of

the Americans. First Lord of the Treasury, George Grenville, justified the

taxes saying that they would go “toward defraying the necessary expenses of

defending, protecting, and securing the said colonies and plantations.” From

our early days, taxes have vexed Americans. A particularly odious tax on the

colonies was the Stamp Act of 1765, covered in last week’s blog. Local Sons of

Liberty began to organize against the rising “tyranny” of the British over

colonial matters.

|

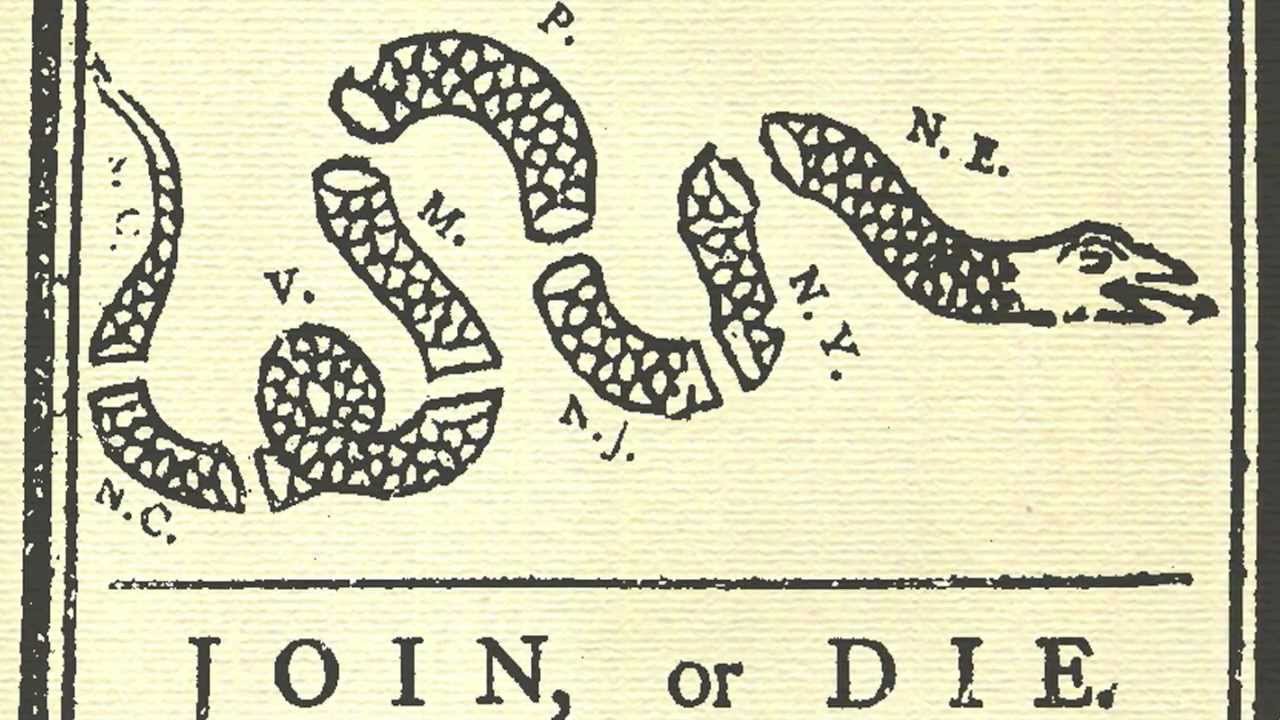

| Ben Franklin's call for unity during the protest against King George III and Parliament. (From Franklin House exhibit at Independence NHP) |

Revolutions need many elements to succeed. They need a

perceived threat to motivate people to rebel. They need talented leaders to

take charge and figure out how to rebel. They require a network of

communication to spread the word. And they need luck.

Talented writers fanned the flames of rebellion and

justified the challenge to the British and King George III. Virginians Patrick

Henry and John Dickinson, Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin, and Bostonian Samuel

Adams stoked popular resentment with pamphlets, broadsheets, and articles

decrying British tyranny and rallying the public with slogans such as “Taxation

without representation is tyranny,” and “Give me Liberty or give me Death.” From

leaflets to popular songs sung in taverns, the rebels organized against England. The patriots were lucky with such talented publicists.

Building on the growing discontent, rebels started

boycotting British imports. Sassafras tea replaced British tea as the protestors’

drink of choice. Women made garments out of homespun cloth, merging fashion

with defiance. Patriots organized militia to resist England. In Massachusetts,

almost all men between sixteen and sixty served in their town’s militia, with

the younger men serving as a rapid response force, nicknamed the Minute Men. All

knew that once open rebellion started, they would face the best military in the

world.

|

| Political cartoon showing the English forcing tea down an American (From exhibit at Minute Man NHP) |

What did the rebels want? They fought for independence from an

oppressive regime; for equality (for white males with property); and for

representation in government. Newly arrived from England, Thomas Paine published

the influential Common Sense in January

1776. In it, he wrote:

It is not in the power of Britain

to do this continent justice: … for if they cannot conquer us, they cannot

govern us.… Independency means no more, than, whether we shall make our own

laws, or, whether the king, the greatest enemy this continent hath, or can

have, shall tell us, "there shall be no laws but such as I like.”

Cries for rebellion like Payne’s unified the disparate

colonies into a continent, into a whole land. Granted, the thin line of English

settlement along the eastern seaboard ignored the rest of North America continent; nonetheless,

colonials started seeing themselves as part of a larger country fighting against

a corrupt government.

In my tour of Independence Hall in Philadelphia led by

Ranger Greg, he mentioned militia Captain Preston’s reason about why they took

up arms against the King. Was it taxes? No. Was it the Boston Massacre? No.

Preston said they fought because those people in England felt that we Americans could no

longer take care of our own business, we could no longer govern ourselves. That

is why he and his fellow soldiers rebelled.

The First Continental Congress met at the Carpenters’ Hall

from September 5 to October 10, 1774 to respond to the Punitive Acts (aka the

Intolerable Acts) that Britain enacted due to the Tea Party. General Gage

placed Boston under martial law. The Congress, with representatives from all

the colonies but Georgia, petitioned King George III to remove these acts and

soldiers from the colonies. They then adjourned with the understanding that

they would meet again if the King rejected their petition. The King was not

amused.

Revolt ignited that April morning north of Boston. After the

British attacked the militia at Lexington Green, they continued to Concord. Nearby

Minute Men swarmed to the sounds of gunfire as the Redcoats searched for arms

and ammunition. When the militia saw smoke coming from Concord, they feared

that the British had started to torch the town. They charged the North Bridge

occupied by the Redcoats and exchanged fire which killed two Minute Men and

eleven English soldiers. British Colonel Francis Smith ordered his men to

retreat to Boston.

|

| North Bridge at Concord where the shot heard 'round the world occurred (Photo by Hunner) |

A mile east of Concord at Meriam’s Corner, a narrow bridge

across a creek created a bottleneck for the British, and the gathering militia,

hiding behind fences, walls, and trees, started picking off the enemy. More

militia joined the fray and forced the English to run a gauntlet of deadly

gunfire as they retreated to Boston. Near Lexington, the British column faced

the men they had attacked that morning who exacted retribution from the Regulars.

A British officer wrote about their retreat:

The Rebels

kept the road always lined and a very hot fire on us without intermission; we

at first kept our order and returned their fire… but when we arrived a mile

from Lexington, our ammunition began to fail … so that we began to run rather

than retreat in order.[1]

Inconceivably, the ragtag group of colonial militia had forced

the Redcoats to flee in disorder. The Regulars ran into reinforcements at

Lexington sent from Boston or their retreat would have been worse.

|

| The retreat from Concord (From Minute Man NHP exhibit) |

The engagement shocked the British —almost three hundred men

killed, wounded or missing, and their forces now under siege in Boston. The Minute

Men suffered ninety-three killed or wounded. As an irregular unit, the militia

inflicted serious damage to the best army in the world by using guerrilla tactics

learned from fighting Native Americans in the woods. This would be a different kind of war.

After the first skirmishes near Boston,

conflicts erupted at Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point in New York. Then, on

June 17, militia from the Boston area defended the strategic heights above Charlestown

from a Redcoat assault. During the Battle of Bunker Hill, a first wave of 2,200

Regulars struggled uphill over fences and hastily constructed bulwarks. Volleys

of bullets rained down from above and forced the Redcoats to retreat. They charged

again, and again the militia fought them back. The third charge proved successful

for the Redcoats as the Patriots started to run out of ammunition. The British suffered

1,054 casualties including 232 dead while the Americans had only 400 dead,

wounded, or missing. British General Clinton complained: “A dear bought

victory—another such would have ruined us.”

|

| The vicious battle for Bunker Hill (From Bunker Hill exhibit at Independence NHP) |

Several consequences came out of these first armed clashes.

First, with cold weather approaching and surrounded by a hostile force, the

British abandoned Boston and retreated by boat to Halifax, Canada where they

wintered. Second, the British generals became more cautious in engaging the home

grown militia whose atypical combat style proved effective. Third, the British

decided to counter this rebellion with a show of force and sent their largest

contingent of soldiers up to that time anywhere for next summer’s campaign. Finally, the Continental

Congress called for all able bodied men to join the militia.

Not all Americans joined the rebellion. Perhaps a third of

the colonials wanted rebellion and freedom from England while another third

remained loyal to the king. The rest stayed neutral, but this was as much a

civil war as a unified struggle against the British. Finally, these Boston battles

sparked the years of combat and destruction as armies chased across the

colonies, killing one another, and often destroying whatever lay in their

paths.

In 1775, the Second Continental Congress convened in May and

in response to the fighting in Boston, declared the colonies independent. They

also organized the defense of the colonies as combat rang out in Boston and elected

George Washington to lead the nascent Continental Army. At the City Tavern, at

Quaker meetinghouses, in Carpenter’s Hall, debates rang out about whether to

rebel and if so, what to put in Parliament’s place.

|

| Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia (Photo by Hunner) |

|

| City Tavern in Philadelphia (Photo by Hunner) |

The Minute Man National Historical Park was created on

September 21, 1959 when President Eisenhower signed its enabling act. The sites

connected to the Revolution in downtown Philadelphia was designated as

Independence National Historic Site in 1934 and added as Independence National

Historical Park in 1938.