Minidoka National Historic Site

|

| The reconstructed watchtower at Minidoka NHS (Photo by Hunner) |

In south central Idaho, the NPS is restoring a field of

dreams. At the site of a World War II internment camp for Japanese-Americans and

Japanese residents at Minidoka, NPS staff and volunteers have recently built a

baseball field among the worn buildings, the collapsed root cellar, and the crumbling

concrete pads that once housed 10,000 “evacuees” who were in fact prisoners of

the US government. From August 1942 to October 1945, Japanese and

Japanese-Americans from the exclusion zone of Alaska, Washington, and Oregon

lived in tar paper buildings and created a community which became

self-sufficient. And played baseball.

I visited Minidoka on the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend. I

was surprised by the number of visitors to this isolated rural place. Cars of

local people drove up, a group on rugged ATVs stopped by, and many listened to

the two Japanese-Americans who had come to remember their past on this weekend

of remembrance. Stan Iwakiri had brought his family to visit the site which he

does annually. I caught them just as they were leaving. He was three months old

when his family got off a train at nearby Eden, rode a bus to Hunt Camp as it

was called, and lived for the duration of the war. His father was a logger in

the Seattle area and because of Executive Order 9066 signed by President

Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, got caught in the sixty mile corridor along the

Pacific coast which excluded people of

Japanese ethnicity. At the entrance to the historic site, Stan pointed to black

lava rock ruins of two adjacent buildings. He said: “One was the police station

and the one next door the welcome center.” We exchanged a look, and then we

both laughed.

|

| Stan Iwakiri who arrived at Minidoka at the age of 3 months with his family (Photo by Hunner) |

The other Japanese American citizen there on Memorial Sunday

asked for anonymity. She was born at Minidoka and invited me to follow her and

her friends to the Honor Roll, Block 22, and the baseball field, which she had

helped rebuild that weekend.

Minidoka was one of ten War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps

used to carry out the government's system of detention of persons of Japanese ethnicity,

mandated by Executive Order 9066. The Order eliminated the constitutional

protections for citizens of due process and violated the Bill of Rights.

Two-thirds of the 120,000 persons of Japanese descent incarcerated in American

concentration camps were American citizens, an act that reflected decades of

anti-Japanese discrimination and then war time propaganda.

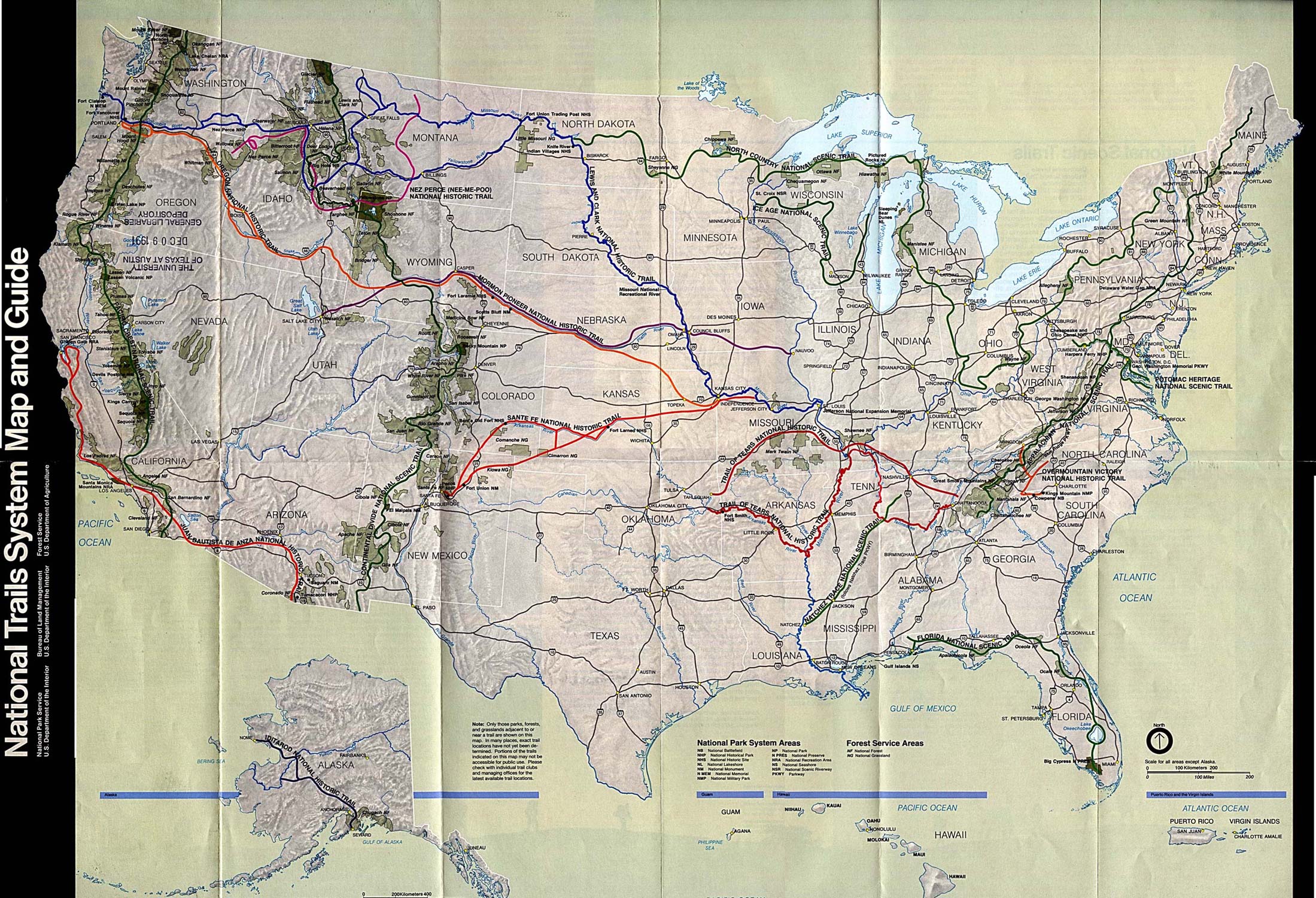

| WRA camps during World War II |

The WRA used Bureau of Reclamation land for this camp. As an

instant city, Minidoka by the end of the war was the seventh largest city in

Idaho. The Minidoka Relocation Center was a 33,000 acre site with more than 600

buildings. In the spring of 1942, the Morrison-Knudsen Company from Boise

received a contract worth $4,626,132 to put up thirty-five residential blocks,

each block with twelve barracks. Each 20 x 120 foot barrack had six rooms for

families or groups of individuals. Each residential block had a mess hall, a

recreation hall, and an H-shaped lavatory building with toilets, showers, and a

laundry. The small city also had a 197 bed hospital, a library, two elementary

schools, a junior high and a high school with 1,225 students, stores, barber

and beauty shops, a watch repair shop, a fish market, sport teams, a recreation

hall shared by churches, swing bands, and movies, and two fire stations manned

by the internees. Additionally, to provide for the 10,000 internees, the camp

had seventeen warehouses, a motor repair shop, and administrative offices. It

was in operation from August 1942 until October 1945.

School children at Minidoka (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/) |

Wrenched from their homes on short notice and allowed only

one or two suitcases, many of these U.S. citizens were in shock when they

arrived in Minidoka. As one internee related: “When we first arrived here we

almost cried, and thought that this is the land God had forgotten. The vast

expanse of nothing but sagebrush and dust, a landscape so alien to our eyes,

and a desolate, woebegone feeling of being so far removed from home and

fireside bogged us down mentally, as well as physically.”[1]

| Unloading from a bus at Minidoka (Courtesy http://arcweb.sos.state.or.us/) |

Amazingly, by the fall of 1943, Minidoka was self-sufficient

in food production, and even sent excess produce to other WRA camps. The people

at Camp Hunt turned a sage brush desert into a cornucopia which that year produced

979,770 pounds of potatoes, 79,325 pounds of carrots, 101,814 pounds of

cabbage, and turned out 1,000 eggs a day. The next year, Minidoka harvested 7.3

million pounds of produce. The elders at the camp told others “Shikataga nai,” meaning “There is

nothing we can do about it so make the best of it.”

Some of the men in camp enlisted and fought in Europe. These

soldiers are recognized at the Honor Roll. Erected among the lava rocks that

held a victory garden, the woman who was born at Minidoka showed us the Honor

Roll. It was built to acknowledge the young men and women from the camp who

served in the military. Despite their and their families’ incarceration at

home, Japanese Americans enlisted and fought in Europe and saw some of the

bloodiest action in the Italian campaign. In fact, Minidoka had the highest

percentage of internees from the ten camps to serve in the military. The

Japanese American U.S. Army unit, the 442nd Regiment, also earned the most medals of

any unit its size with 9,486 Purple Hearts. The Honor Roll at the entrance to Minidoka pays tribute

to those who fought and died for a country who had incarcerated them.

|

| The Honor Roll (Photo by Hunner) |

One of the ways to make the “best of it” was through playing

baseball. Baseball and softball offered an escape for some of the over 10,000

people who lived at Minidoka. Samuel O. Regalado's book Nikkei Baseball states: ”To

the evacuee, sport was not an ‘innocuous aspect of life’; it was an essential component

to their mental and emotional survival in the camps.” Local baseball coverage in

the camp newspaper rivaled stories about their fellow Japanese Americans in

combat.

|

| Newly rebuilt Baseball diamond (Photo by Hunner) |

Soon after they arrived, internees started playing ball. Fields

sprang up around the Minidoka camp, and youngsters and adults of both sexes hit

the diamonds. The camp paper, the Minidoka

Irrigator, reported on September 11, 1943: "Yup! Old man baseball

reigns supreme among our dads and have helped make life in this camp more

pleasant for him. Without the game, he'd be lost and idleness would reign

supreme instead of baseball. They also did a swell job in providing some

exciting games for us and their sportsmanship and spirit were tops. Hats off to

our 'old men’." That same month, the

newspaper reported that young women had organized into softball teams representing

their home towns of Portland and Seattle and played against each other. The

newly rebuilt baseball diamond recalls an essential part of life at Camp Hunt

and evokes its own field of dreams.

Incarcerating U.S. citizens because of their ethnicity

violated their constitutional rights. Targeting any citizens,

whether they are European-Americans, Japanese-Americans, Native-Americans, Mexican-Americans, or

Muslim-Americans denies their rights and harms our country. The diversity of

the United States makes us stronger, not weaker, and succumbing to demagoguery

because of a national emergency or a political campaign undermines our Constitution

and our nation’s ideals. Our best idea, and we have had many, is the

declaration that all men are created equal and are endowed with inalienable

rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. To subvert those rights

threatens our best idea.

Minidoka National Historic Site was created in 2001.

|

| Minidoka's FIeld of Dreams (Photo by Hunner) |