The rupture had happened, the first cannons fired. Now how to

put soldiers in the field ready to fight? And not just fight, but win? In this

posting, we will look at two early battles in the Civil War that foretell the

bloody future as well as the broad shadow it cast upon the continent —the First

Battle of Manassas and the Confederate invasion of New Mexico culminating in

the Battle of Glorieta east of Santa Fe. Manassas and Glorieta offer ample

examples of how each side made mistakes and capitalized on the mistakes of the

other side.

|

| A Confederate cannon pointed at the Union stronghold of Henry House. (Photo by Hunner) |

In the summer of 1861, as the nascent armies formed and

moved towards each other, each side came up with their master plan. Lincoln and

his generals decided to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond in Virginia

and attack the rest of the South through the Ohio, Tennessee, and Mississippi

Rivers. Davis and his Confederate generals chose a strategy similar to that of George

Washington during the Revolution —fight a defensive war and keep the South’s

armies in the field. With these best laid plans and with politicians and

newspapers crying out for action, the North and South grappled near a stream

called Bull Run.

Armies at the beginnings of wars often fail to fight

effectively. Generals struggle to adapt to new weapons and tactics,

inexperienced soldiers face death and mayhem, jealousy and infighting with

officers all contributed to mistakes that cost men their lives and lost each

side opportunities to seize a crippling victory and put an early end to the

war. Manassas was just the beginning of the North and the South figuring out

how to fight.

Two classmates from West Point’s class of 1838 commanded the

opposing armies at Manassas. General P. G. T. Beauregard from Louisiana had

distinguished himself in the Mexican American War and in 1861 was the head of

West Point. He left there to take charge of the Confederate forces in Virginia.

He had to protect Richmond and threaten Washington. Beauregard’s army on the

eve of battle amounted to 20,000 troops, but Johnston’s soldiers in the

Shenandoah Valley rushed to the battle at a key moment.

The commander of the Union forces, General Irvin McDowell,

also served in the Mexican American War and was an instructor at West Point. On

July 1, 1861, the Union Army had 186,000 soldiers, of which McDowell devoted

30,000 to attack Beauregard. Both sides thought that an early victory would led

to a quick war. Both looked to Manassas for that victory.

|

| A replica of the Henry House is the white one on the right This would have been the view that Confederates had as they advanced on this strong hold of Union cannons. (Photo by Hunner). |

The Union’s march on Manassas slowed due to ambling troops

and supply wagon delays. Men carried only three days of rations with not enough

supply trains to deliver more. On July 21st, McDowell’s troops tried

to skirt around the Confederate left, but scouts saw the glinting of the sun

off of weapons in the slow moving columns and warned Beauregard that his flank

was getting turned. Then the two sides fell on each other with fury and fear.

At first, Union soldiers and cannonry pushed the Confederates back toward the

railroad line. An eager battery led by Capt. James Ricketts advanced to the

hill near the Henry House and blasted shrapnel into the advancing Confederates

as sharpshooters picked off the Union artillery men.

Enter General Thomas J. Jackson. Also a veteran of combat

during the Mexican American War, Jackson commanded of a large contingent of Virginians.

At Manassas, the arrival of his troops in the afternoon rallied the retreating

Southerners and gave rise to “There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally

behind the Virginians!”

|

| Statue of Stonewall Jackson at the spot he stood to rally the Confederates at the First Battle of Manassas (Photo by Hunner) |

More Confederate troops arriving by train from the

Shenandoah Valley flooded onto the battlefield and started pushing Union

soldiers back. Perhaps the mad dash to the rear by a horse drawn wagons dispatched

to get more ammunition for Ricketts’ cannons set off the retreat among the

green Union troops.

|

| Ricketts' batteries near Henry House (Courtesy Manassas NBP web site) |

The number of casualties shocked everyone. Much worse would

come. Manassas smacked away any notion that this would be a quick war.

|

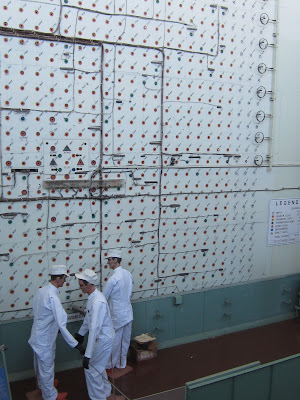

| Confederate artillery proved vital for their victory at Manassas (Photo by Hunner) |

After Manassas, most northern states quickly responded to

Lincoln’s call for more troops, but they saddled the federal army with a major

flaw. Troops voted for their officers who sometimes had little combat or even

military experience. Many Confederate officers graduated from West Point or

fought in the Mexican American War. At first, Southern troops had better

leadership, while Northerners had better engineers.

An important lesson learned at this early point was the

importance of railroads in the Civil War. They provided rapid deployment of

troops as well as supplied the necessary materiel and food to keep men

fighting. Railroads also brought the battered wounded back to hospitals. Railroad

junctions proved vital for rapid responses to wide flung theaters of the war.

Another early lesson was to standardize uniforms and flags to prevent confusion in combat about whether you were fighting was friend or foe.

In the same month as the First Battle of Manassas, action

out West also gave the South an early victory. On July 24th, 1861, 250 Texans invaded

southern New Mexico and captured the village of Mesilla in a brief exchange of

muskets and mountain howitzer fire. That winter, General Sibley and his 2,500

men reinforced Mesilla with the ultimate goal of capturing the gold and silver

mines in Colorado. If that went well, they wanted to continue onto the ports in

California.

Once assembled at Mesilla, the Confederates marched up the

Camino Real to Santa Fe. They avoided the strongly defended Fort Craig but did beat

back the Union forces who guarded the ford of the Rio Grande at Valverde on

February 21st. Union troops retreated before the advancing troops, burning

supplies along the way. Within a few weeks, a Confederate flag flew over the

Palace of the Governors on the central plaza in Santa Fe.

|

| Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe (Photo by Hunner) |

After resting in ancient Santa Fe, the Confederates headed east

along the Santa Fe Trail towards Colorado. Twenty-five miles out, they ran into

Union soldiers and cannons at Glorieta. The Union forces fell back, waiting for

reinforcements and getting closer to their own heavily defended Fort Union

fifty miles away.

|

| Live fire demonstration of a Mountain Howitzer at Glorieta (Courtesy Pecos NHP website) |

On March 28, 1862, the two sides with about 1,300 soldiers

each clashed along the Santa Fe Trail. By day’s end, Union forces had retreated

another mile or so. As both sides bedded down, news came to electrify the New

Mexicans and Coloradans. The previous night, a column of Union soldiers led by Major

John Chivington slipped around the Confederates and found the 100 plus wagons

that held all of the Texans’ ammunition, supplies, and personal belongings. Although

the South was winning on the battlefield, it had to retreat back down the

Camino Real with little food and low morale. Several years later, Chivington

led the raid at Sand Creek.

Why mention the Battle of Glorieta along with First

Manassas? First, from Virginia westward, across farmlands, through dense

forests, and over swollen rivers and parched deserts, armies fought in large

and small battles. This was a continental wide conflict with many side theaters.

In fact, two weeks after Glorieta, the Battle of Shiloh on the Tennessee River

began to pry open the South to water borne invaders from the North. We will go

to Shiloh and Corinth in next week’s blog. Second, the Union forces that remained in New

Mexico then targeted Apaches and Navajos for removal to an inhospitable stretch

of the Pecos River far away from their ancestral homelands. Third, as a proud

New Mexican, I take any opportunity to tell the history of my state.

The Civil War did not go well at first for the North. Both

sides bivouacked for the winter of 1861-62, recruited and trained new soldiers,

and looked for the weaknesses in their enemies. Each side hoped for decisive

victories in the coming year.

The ruins of the Pecos Pueblo became a National Monument to

preserve the Indian town and the Spanish colonial church. In 1990 with the

addition of the Forked Lightening Ranch and the Glorieta Battlefield, it became

the Pecos National Historical Park.