After the Confederate victory at Manassas and its invasion

and retreat from New Mexico, both sides hunkered down, went into winter

headquarters, recruited and trained new soldiers, and sought ways to implement

their overall strategies. The focus of this posting is the Union campaign into

the South using the waterways of the Ohio, Tennessee, and Mississippi Rivers.

We will look at the Battle of Shiloh this week and Antietam next week.

The woodlands of the South hindered overland travel. The

thick forests slowed foot and wagon passage and prevented the rapid movement of

large numbers of soldiers and materiel. A better way, used by humans for

millennia, is water. The major rivers that coursed through the South -- the

Mississippi, the Tennessee, the Cumberland, and the Ohio -- opened up wide

avenues for transportation and invasion. River travel became so important in

this theater of the war that the Union leased almost 150 steamboats to

prosecute the war.

|

| Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River (Photo by Hunner) |

The Union forces pried open the Tennessee River in February

1862 when General Grant’s troops captured Forts Henry and Donelson and forced

the Southern troops to abandon northwestern Tennessee. Once those forts fell,

Union troops steamed upriver in paddle wheeled riverboats to Pittsburg Landing,

about thirty miles north of Corinth Mississippi. Corinth, a key railroad

junction, connected the Deep South with its north and west and proved a prime

target for the North to divide and conquer the South.

General Grant had fought gallantly in the Mexican-American War but grew bored with the peacetime Army and his drinking led to his resigning from the military. Once the Civil War started, he took over first supplying troops and eventually leading the soldiers from his state of Ohio. At Shiloh, he had 40,000 soldiers.

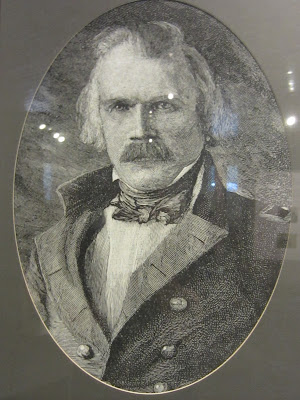

General Grant, left, and General Johnston below, faced each other at Shiloh.

Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston had other ideas. He

marched his 44,000 men from Corinth to force the issue on open ground around

the small Shiloh Church, near the Union beachhead at Pittsburg Landing. Over

the thirty-four hour battle, nearly 24,000 men were killed, wounded, or

captured.

Grant had orders not to engage the enemy until General Don

Carlos Buell’s troops coming from Nashville joined him. But on April 6th,

a Union patrol encountered a Confederate picket line around 5 am. They

exchanged gunfire for an hour, and then General Johnston launched his Army of

the Mississippi against the Union forces. For the rest of the morning, rebel troops

pushed back the Northerners’ three-mile wide front in vicious fighting.

At the

Hornet’s Nest (so named for the buzz of bullets flying through the air) in the

center of the Union line, forces defended at least three assaults. After six

hours of intense and bloody combat, the Northerners still held the dense oak

thicket at the center of the battlefield. Confederates brought artillery from

other parts of the battlefield and pounded the Hornet’s Nest from 300 yards

away into submission. 2,200 Union soldiers surrendered due to “the Confederates

[concentrating on them] the greatest collection of artillery yet to appear on

the American Continent.”

|

| On top, the Hornets' Nest point of the battle. Above, Confderate cannons lined up to pound the Hornets' Nest at the tree line in the distance. (Photo by Hunner) |

After capturing the Hornet’s Nest, Johnston’s forces

advanced, threatening the Union base at Pittsburg Landing. Northern soldiers

straggled back to the earthworks around the landing all afternoon and aided by

a heavily wooded ravine in front of them, held their position as the day ended.

Johnston and his staff predicted an easy victory the next day.

|

| The battle map toward the end of the first day, April 6th. (From exhibit panel on driving tour of battlefield). |

But the battle was already turning against the men in gray

as the advance units of Buell’s Army of the Ohio were ferried across the

Tennessee River and joined the defense of Pittsburg Landing. That Sunday night,

more than 20,000 Northerners crossed the river.

|

| Steamboats supplying the Union war effort along a river in the SOuth (From exhibit at the Shiloh Visitors Center). |

On April 7th, Grant’s and Buell’s Divisions

attacked the Confederates and drove them back. Riding near the frontline, Johnston

was struck by a bullet which severed his femoral artery, and he died on the

battlefield. Thus fell the highest ranking officer from either side during the

Civil War. Beauregard, who had already distinguished himself at Fort Sumter and

at First Manassas, took over command of the Southerners. Pressed by the fresh Union

troops, Beauregard ordered his troops to leave the field around 4 pm. They

retreated to Corinth.

|

| Gerneral PGT Beauregard who replaced Gen. Johnston (From exhibit in Shiloh Visitor's Center) |

A total of 23,746 men were killed, wounded, or missing. Both

sides suffered greatly but “the battle mutilated the western army of the

Confederacy, which lost key officers, 10,000 men, and perhaps its best

opportunity to destroy a Union army in the field.”

The Union army followed the Confederates to the railroad

town of Corinth, Mississippi for a final reckoning. Two of the most important

railroads in the Confederacy crossed at Corinth—the Memphis & Charleston

and the Mobile & Ohio.

|

| The crossroads at Corinth today (Photo by Hunner) |

They linked the Mississippi River to the Atlantic

seaboard and the Gulf Coast to Kentucky. This made Corinth the most strategic

transportation hub in the western part of the Confederate states. Under siege

from April 29 to May 30, Confederate troops built several miles of rifle pits,

trenches, and earthworks around the small town. They abandoned Corinth in May

but returned at the beginning of October to retake the town. One observer said:

“In places, you could walk on the dead.” This intense assault by the Confederates

on the earthworks that they had initially built earlier that spring failed with

8,000 men combined from both sides killed, wounded, or missing.

At the same time as the attack on Corinth in October 1862, a

Confederate force under General Bragg marched through Kentucky toward

Cincinnati, more important to the Union than Chicago as an industrial and

railroad center. If the South could cross the Ohio River and capture Cincinnati,

they could accomplish subject the Union with what Grant was trying to do to the

Confederacy. Bragg’s invasion failed at the Battle of Perryville. As military

historian John Keegan explains about the defeats at Corinth and Perryville: “the

failure in the West was a grave blow to the Confederacy, reducing their range

of strategic options to the well-worn pattern of keeping alive Union fears of

an advance against Washington or feints at Pennsylvania and Maryland, theaters

where the North enjoyed permanent advantages.”

After May 1862, slaves who had fled their plantations found

refuge in Corinth. Called “contrabands of war,” some 6,000 African-American

ex-slaves created a thriving community of homes, a church and school, a

hospital, and a cooperative farm. From the Corinth Contraband Camp, nearly

2,000 ex-slaves enlisted in the Union’s First Alabama Regiment of African

Descent to join the over 150,000 Blacks who fought in the Civil War.

|

"Contrabands of War" African Americans who fled planations and found

refuge behind Union lines (From exhibit at Cornith Civil War Interpretive Center) |

|

Freed slaves fighting for the Union

(From Corinth Interpretive Center) |

The soldiers required special care from the devastation that

minnié

ball bullets and artillery shells wreck on the human body. To care for the

wounded, each regiment of 200-300 soldiers had a surgeon, an assistant surgeon,

and a hospital steward. During a battle, the number of casualties often overwhelmed

the surgeons, who treated them just behind the front lines. Triage was fast.

Soldiers with minor wounds underwent dressing and then returned to combat.

Those more seriously wounded were evacuated to a field hospital further away

from the battle, often a barn or residence.

|

| Wounded outside a field hospital in the Peninsular Campaign in Virginia, 1862 (From exhibit at Corinth Civil War Interpretive Center) |

|

| The surgeon's tool kit for treating the wounded from combat ( From exhibit at the Corinth Civil War Intrepretive Center) |

Shattered limbs had little chance of healing as the many splinters of bone and open wounds proved difficult to treat. Amputation was rapid, partially because the ether or chloroform wore off quickly and partially because new casualties arrived constantly. Without antibiotics, gangrene from a wound could set in and kill a patient. If a soldier survived the cutting off of a limb, they still could succumb to complications like pneumonia.

Medical officers from both armies cared for the 16,420

wounded men after Shiloh. Once stabilized, most of the 8,408 Union wounded went

by steamboat to Savannah, Tennessee. Most of the Confederate wounded first went

to Corinth and then by railroad to other towns and cities in the western

Confederacy. At Corinth, almost every building served as a hospital to care for

the men. Churches, aid societies, and soldiers’ families rushed medical

supplies and people to help. As with most Civil War battles, nearby towns

served as hospitals for months afterward.

|

| Kate Cumming, a nurse at Shiloh after the battle (From exhibit at the Shiloh Visitors' Center). |

One of those who heeded the call for help was Kate Cumming,

whose brother fought at Shiloh. Here are some quotes from her journal: “Corinth

is more unhealthy than ever. The cars have just come in, loaded outside and

inside with troops…they have endured all kinds of hardships; going many days

with nothing but parched corn to eat, and walking hundreds of miles…without

shoes.” Another entry: “I have been through the ward to see if the men are in

want of anything; but all are sound asleep under the influence of morphine. Much

of that is administered; more than for their good…. I expressed this opinion to

one of the doctors; he smiled, and said it was not as bad as to let them

suffer.” Here is another observation from Kate: “There is a Mr. Pinkerton from

Georgia shot through the head. A curtain is drawn across a corner where he is

lying to hide the hideous spectacle, as his brains are oozing out.”

| Bernard Irwin's field hospital at Shiloh lcreated a new way to take care of the wounded after a battle that was used throughout the war. (From exhibit at Shiloh Visitors' Center) |

The battle at Shiloh Church and the subsequent siege and

occupation of Corinth shifted the war in the West. Vital transportation and

communication lines were severed for the Confederacy, and the paths to both Chattanooga

on the Tennessee River and Vicksburg on the Mississippi River lay open to Grant

and his men. If the Union could crack Chattanooga, a path to Atlanta would open

up. But Chattanooga would prove a tough nut to crack.

|

| Steamboats played a vital role in the river campaigns in the South. (From exhibit at the Shiloh Visitors' Center) |

Shiloh became a National Military Park in 1894 managed by

the Department of War and was transferred to the National Park Service in 1933.