As with the post on the Sand Creek Massacre, this history contains

accounts of graphic violence. Do not read any further if this will upset you.

|

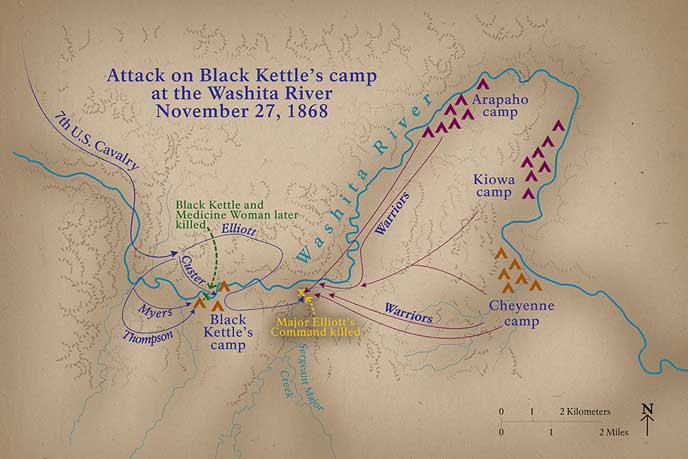

| The 7th Cavalry attacking Black Kettle's camp on the Washita River (From the exhibit at the Washita Battlefield NHS) |

On November 26, 1868, the Peace Chief Black Kettle had just

returned to his Washita River camp from a strenuous 100 mile mission through

the snow to request permission to move his camp closer to Arapaho, Kiowa, and other

Cheyenne tribes downriver. Permission was denied. His wife, Medicine Woman

Later, uneasy with the rumors of U.S. troops in the area, wanted to move that

night. She had good reason to feel uneasy. In 1864, at Sand Creek in Colorado,

U.S. troops had attacked their peaceful camp, killed 125, and shot her nine

times. She survived, but now at their winter camp, she had a premonition. The

council of elders decided to wait until the next morning to move.

|

| Map of Battle (From Washita Battlefield NHS web site) |

|

| Looking at the hills to the northwest over which Custer and his troops rode to attack the camp among the trees in the middle of the picture (Photo by Hunner) |

|

| Some Cheyenne hid in the tall grass to escape the soldiers (Photo by Hunner) |

|

| Place where horses and mules were slaughtered (Photo by Hunner) |

With ammunition running low and a growing force of enraged

warriors nearby, Custer feinted a move to go downriver which sent the warriors

retreating to protect their own camps. Relieved of a possible counterattack,

the 7th Cavalry and their prisoners stole away into the fading

light.

This is the second act in the tragedy of the southern plains

Indian War. As Ranger Joel Shockley recounted, the first act happened at Sand Creek. When Col. Chivington and his soldiers attacked Black Kettle’s camp of

peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho in 1864 at Sand Creek, a Plains War erupted that

lasted for years, culminating in the Battle at Little Big Horn (Joel’s third

act). In response of the Sand Creek Massacre, warriors from the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers

rampaged across the southern Plains to avenge their fallen comrades and family

members. Peace treaties came and went, and Black Kettle signed some of them,

but he had little control over the attacks by the warriors.

Francis Gibson, a lieutenant in the 7th Cavalry,

later estimated that between August and November in 1868, 117 people were

killed in the southern plains by the Dog Soldiers, with others scalped or captured,

and almost 1,000 horses and mules stolen. As Western historian Paul Hutton said

in the movie at the Washita visitors’ center: “The Army was humiliated. This

was the Army that had defeated Robert E. Lee.” Something had to be done.

The Commander in charge of the Department of the Missouri,

Major General Philip Sheridan, called for total war against the Indians. His

aide-de-camp, Schuyler Crosby wrote: “The General’s policy is to attack and

kill all Indians wherever met and to carry war into their own villages so that

they will have to withdraw their marauding bands for the protection of their

own families.”[1]

|

| Lt. Col George Custer as he looked during the winter campaign at Washita (https://www.nps.gov/common/uploads/photogallery/imr/park/waba/) |

As I left the film about the massacre, I noticed that the

other guy in the room had a t-shirt from Fort Pulaski. I struck up a

conversation with Tim Sprano from Lynchburg, Virginia. He is a veteran park

goer, having visited 371 of the 412 in the system over the last fifteen years.

He teaches mathematics at Liberty University, but his other passion is our

national parks. He remarked that every park has its own reason to exist, so

take what it gives you. Here at Washita, he commented: “Obviously, we wouldn’t

do stuff now that they did 100 years ago. We have different values today than

of the past so it’s important to see and hear the whole story.”

After the movie, Park Rangers Joel Shockley and Richard Zahm

spent over an hour chatting with me about what happened at Washita. Richard

said this was an important site because people truly learn about our past

here-- people who just stop by to stamp their NPS passports end up staying here

all day. He said: “It’s so much more complicated than just cowboys and

Indians…. I thought when I came out here, it would be a lot of black and white

and it’s not. There are good guys and bad guys on all sides.”

Joel agreed: “This is one of the best kept secrets in

American history. It is far more complicated. This was like the Oklahoma City

bombing for the tribes or like 9/11. There were not just Cheyenne here, there

were a lot of Indians involved, and Mexicans too. Half of Custer’s command were

immigrants from Ireland and Germany, a way to become citizens. All these

cultures came together by happenstance…. This is part of your heritage, whether

you have Indian in you, have soldier in you. It’s part of our heritage – all

our warts and blemishes.”

[3] After the Civil War, the Army used the tactics and weapons to wage total war to force Indians to move to reservations and kill those who refused to go. This last chapter of the Indian Wars in North America played out over the decade or so right after the Civil War. The legacy of conquest lives with us today, and as Richard, Joel, and Tim note, it is a complicated story viewed from our 21st century eyes.

|

| NPS Ranger Richard Zahm (Photo by Hunner) |

[3] After the Civil War, the Army used the tactics and weapons to wage total war to force Indians to move to reservations and kill those who refused to go. This last chapter of the Indian Wars in North America played out over the decade or so right after the Civil War. The legacy of conquest lives with us today, and as Richard, Joel, and Tim note, it is a complicated story viewed from our 21st century eyes.

Everywhere I have traveled in Driven by History, I have run

into the deep heritage of our land, which starts with Native American peoples.

They had rich and complex civilizations before Europeans arrived, they lost

much of their ancestral lands and their culture, and they are still here.

The Washita Battlefield became an Oklahoman state park in

October 1966 and a National Historic Site on November 12, 1996.

Being a historian of the American West, what happened to the Native American people is a tragic and largely forgotten part of our history. Thankfully the park service is helping to keep it alive

ReplyDelete