|

| The valley floor at Yosemite with El Capitan to the right, Half Dome center in the distance, and Bridal Falls to the right. (Photo by Hunner) |

The spectacular landscape of Yosemite’s bald domes and deep valleys, of

its crashing waterfalls and rarefied high country vistas took over 100 million

years to create. The dramatic cliffs are made of granite, formed deep in the earth

as molten rock which slowly cooled and solidified into massive stone megaliths.

About sixty-five million years ago, the granite core of the Sierras Nevada

mountains became exposed. Twenty-five million years ago, tectonic forces lifted

and tilted the granite range and formed the tall Sierra Nevadas. Then the

forces of water and ice began to shape the hard stone.

Enter the glaciers. Over the last two to three million

years, ice fields and glaciers at times capped the high peaks and during ice

ages, descended down the valleys to scour and change the landscape. Rivers had cut

“v” shaped valleys, but the grinding of glaciers created “u” shaped ones with

wide level floors filled with glacial sediment. Geologic time is writ large in

the Yosemite Valley.

Human have also left their marks on the Yosemite landscape.

The Ahwahneechee tribe of the Miwok Indians have lived in the Southern Sierras

for perhaps 7,000 years. Moving from the deep canyons to high alpine meadows,

the Ahwahneechee developed a hunter and gatherer life style suited for the high

Sierras. Change came in the early 19th century with contact with

Europeans-Americans. After the Gold Rush brought a flood of miners to the

region, John Savage set up a camp in the foothills which was attacked by the

tribe. In retaliation, a volunteer militia called the Mariposa Battalion fought

and eventually defeated the Ahwahneechee. A lake in the high country where a

major battle occurred was named after Ahwahneechee’s Chief Tenaya. Tenaya and

his tribe were forcibly removed to a reservation near Fresno, but Congress did

not accept any of the eighteen treaties made with Californian Indians in 1851

and 1852. Over the years, even though the U.S. government forcibly evicted the Ahwahneechee

from the Yosemite Valley, tribal members still live in the area.

Some argue that Yosemite is our oldest park. Here’s

why—President Lincoln, in 1864 in the midst of the Civil War, signed the

Yosemite Land Grant, setting aside the Yosemite Valley as a nature reserve run

by California. To be sure, Yellowstone became our first National Park in 1872,

but Yosemite was our first protected place. Lincoln never visited Yosemite, but

his legacy in protecting it place continues to thrill millions of people a

year. Four years after Lincoln designated Yosemite as a nature reserve, John

Muir arrived in the valley.

Already a world traveler, Muir fell in love with Yosemite—with

its high mountains, the Granite Cliffs, the sequoia trees at Mariposa Grove,

and the valley floor. In an essay for The

Century magazine in 1890, he marveled about the beauties of Yosemite.

|

| The high Sierras on Tioga Road (Photo by Hunner) |

About the High Sierra, he wrote: “It seemed to me the Sierra

should be called, not the Nevada or Snowy Range, but the Range of Light. And

after ten years in the midst of it, rejoicing and wondering, seeing the

glorious floods of light that fill it,-- the sunbursts of morning among the

mountain peaks, the broad noonday radiance on the crystal rocks, the flush of

the alpenglow, and the thousand dashing waterfalls with their marvelous

abundance of irised spray,-- it still seems to me a range of light.”[1]

|

| The brow of El Capitan (Photo by Hunner) |

Concerning the Granite Cliffs, Muir exults: “The brow of El

Capitan was decked with long streamers of snow-like hair, Cloud’s Rest was

enveloped in drifting gossamer films, and the Half Dome loomed up in the garish

light like some majestic living creature clad in the same gauzy, wind woven

drapery, upward currents meeting overhead sometimes making it smoke like a

volcano.”[2]

|

| Sequoias at King's Canyon (Photo by Hunner) |

Muir glories in the big trees: “The majestic sequoia, too is

here, the king of conifers, ‘the noblest of a noble race.’ All these colossal

trees are as wonderful in the fineness of their beauty and proportions as in stature,

growing together…. Here indeed is the tree-lover’s paradise, the woods, dry and

wholesome, letting in the light in shimmering masses half sunshine, half shade,

the air indescribably spicy and exhilarating, plushy fir boughs for beds, and

cascades to sing us asleep as we gaze through the trees to the stars.”[3]

|

| Yosemite Valley with Half Dome in the background (Photo by Hunner) |

About the Yosemite Valley, he proclaims: “No temple made

with hands can compare with the Yosemite. Every rock in its walls seems to glow

with life. Some lean back in majestic repose; others, absolutely sheer or

nearly so for thousands of feet, advance beyond their companions in thoughtful

attitudes…. How softly these mountains are adorned… their feet set in groves

and gay emerald meadows, their brows in the thin blue sky, a thousand flowers

leaning confidingly against adamantine bosses, bathed in floods of booming

water, floods of light while snow, clouds, winds, avalanches, shine and sing

and wreathe about them as the years go by!”[4]

Rallying around such words, advocates for Yosemite found

allies in Congress, and Yosemite became a National Park in 1892. But the battle

was not totally won. To continue to protect the sacred places in the Sierras, in

1901 Muir published Our National Parks,

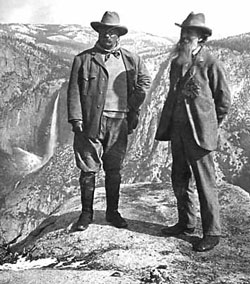

and in 1903, President Teddy Roosevelt visited Yosemite. Muir kidnapped him for

several days of camping out in the high country, to the chagrin of the gathered

politicos who wanted to bend the president’s ear. Together, Roosevelt and Muir,

under the stars around a campfire and hiking over the granite domes, laid the

foundation for a conservation policy that protected some natural resources and

preserved the shrinking wilderness.

|

| President Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir at Glacier Point in 1903 (Photo from NPS) |

The last chapter in Muir’s life ends in a preservation

tragedy. At the north end of the Yosemite National Park lays the Hetch Hetchy

Valley fed by the Tuolumne River. The

growing city of San Francisco coveted the water in that valley and after the

Great Earthquake of 1906, argued and won the rights in 1913 to that liquid

resource. With the rights, the city dammed the Hetch Hetchy and siphoned the

water off to the Bay Area. Muir and the Sierra Club fought hard against this, and

he died a year later, some say a broken man from the loss of this stunning part

of a national park.

|

When I visited Yosemite, the Mariposa Grove of giant

sequoias was closed to the public for rehabilitation. There are almost 500 of these largest living things on earth in the grove, which was included in

the original grant created by Lincoln in 1864. J. Smeaton Chase, an Englishman,

wrote this about Mariposa Grove: “As one stands in the dreamlike silence of

these groves of ancient trees, the solemnity of their enormous age and size

combine to produce a cathedral mood of quietude and receptiveness.”[5]

Since I couldn’t get to the sequoias in Yosemite, I went

south to King’s Canyon to experience these Big Trees. Granted, redwoods are

taller, but sequoias’ trunks are bigger, and those massive trunks retain their girth

as the trees climb. In terms of actual living mass, sequoias have more wood

than redwoods.

|

| The General Grant Sequoia at King's Canyon (Photo by Hunner) |

I arrived at the General Grant tree after a brisk walk from

the nearby campground, late for a Ranger Amber’s talk. This is the second

biggest tree in the world, with the General Sherman tree at Sequoia NP taking

the honors. Between 1,600 and 1,800 years old, the General Grant sequoia takes

twenty people holding hands to encircle its trunk and in a weird statistic,

could hold more than 37,000,000 ping pong balls. Here’s some more stats on the

General Grant: height = 268 feet (82 meters); circumference = 107 feet (33

meters); diameter = 40 feet (12 meters); and weight = 1,254 tons (1,325 metric

tons).

|

| The trunk of a sequoia at King's Canyon. Notice the people on the left. (Photo by Hunner) |

A saving grace for all sequoias is that they burst into

splinters when felled so they are unsuitable for lumber planks. Shingles, yes

and also fence posts, but considering it takes so much effort to cut one down,

the resultant wood is not worth the trouble.

At the end of her presentation, I talked with some rangers about my concerns concerning all the dead trees on the western

slopes of the Sierras. I had read in a Los

Angeles Times story that Sunday that

the U.S. Forest Service estimated the 20,000,000 trees in the Sierra Nevadas

had died since October and 60,000,000 since 2010.[6]

I asked if wild fires could sweep through the groves here, at Sequoia National

Park, and at Yosemite, and destroy these majestic ancient beings. One of the rangers said: “Perhaps we are the last generation to see these monarchs of trees.”

Shocked, I spent the rest of the afternoon wandering around this cathedral of

giants.

|

| A trunk of a massive sequoia at King's Canyon (Photo by Hunner) |

Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia National Parks are

places of immense beauty and spirit. Granite megaliths, ancient trees, deep

valleys, high alpine mountains, tall waterfalls, they establish the sacredness

of wilderness and allow us to commune with natural wonder. They change, as Muir

wrote, our perception of nature and the world around us. Without such parks and

without the people who struggled and continue to work to preserve these places,

we would be a lesser nation and people. Just ask the over 4,000,000 people who

visited Yosemite in 2015 or the 300,000,000 who went to some unit in our NPS

system last year. The parks transcend our differences and unites us around

their natural and historical landscapes.

|

| The Upper and Lower Yosemite Falls, the tallest waterfall in the U.S. (Photo by Hunner) |

Yosemite became a National Park on October 1, 1890 and was

designated a World Heritage Site on Oct. 31, 1984. King’s Canyon was

established as General Grant NP on Oct. 1, 1890 and was renamed and enlarged in

1940. Sequoia NP was created on Sept. 25, 1890

[1] John

Muir, The Treasures of the Yosemite,

(Lane Magazine and Book Company: Menlo Park, 1970), 16.

[2]

Ibid, 48.

[3]

Ibid, 20.

[4]

Ibid, 18-19.

[5]Ardeth

Huntington, YosemiteNational Park: A

Personal Discovery (Mariposa, California: Sierra Press, n.d.), 41.

[6] Los Angeles Times, June 23, 2016, A-1.

_in_1916.jpg/220px-Elizabeth_Thacher_Kent_(1868-1952)_in_1916.jpg)