This week, I drove to history from Indian Removal in the

1830s through several Civil War sites, a whiskey distillery, the Tennessee

Valley Authority, and ended with the Space Race in Huntsville. It’s been a busy

week.

I started out going over the Smokies with a stop at the

Museum of the Cherokee Indians in Cherokee, North Carolina.

|

| Depictions of the three Cherokee leaders, Ortenaco, Cunse Slote, and Wogi, who went to England in 1762 to meet the English King. (From exhibit at the Museum of the Cherokee Indians) |

Since I passed through Oklahoma at the end of

July, I have crossed the Trail of Tears and wanted to see what the Cherokee Museum

said about it. Here’s an interesting irony. A Cherokee ally saved Andrew Jackson’s

life at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend but then as president in the 1830s, he

forced some 16,000 Cherokees from their homelands to walk to Indian Territory

in Oklahoma. They walked across nine states and over 2,000 miles, marshaled by

local and state militias. Estimates vary, but between 2,000 to 6,000 perished

along the way. Later in the week, I stopped by the Cherokee Removal Memorial

Park in Tennessee where 90% of the deportees crossed the Tennessee River.

|

| The crossing of the Tennessee River at Blythe's Ferry, Tennessee (Photo by Hunner) |

I got a taste of the Smokies at the Joyce Kilmer Memorial

Forest. You might remember Kilmer from the poem he wrote called “Trees.” It

begins “I think I shall never see a poem as lovely as a tree.” He later volunteered

for World War I where he was killed by a sniper in the Second Battle of Marne. I

walked through old growth trees and breathed in the rich poetry of the forest.

|

| Old growth trees at the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest. Note the person to the right of the trunk. (Photo by Hunner) |

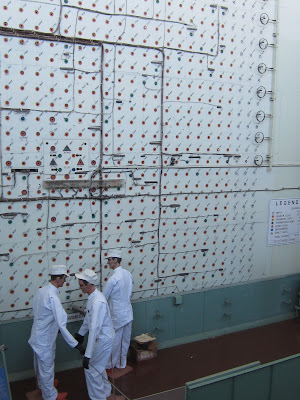

I also dove into World War II and the role that Oak

Ridge in Tennessee played in creating an atomic bomb. I went on a public bus

tour and saw the second nuclear reactor ever built. I am an atomic historian with

a specialty on Los Alamos, so I was glad to learn more about the role that Oak

Ridge played in enriching the uranium that went into the atom bomb.

Thanks Stephen for the informative tour.

|

| The second atomic reactor preserved at Oak Ridge. (Photo by Hunner) |

In Chattanooga, I visited the Chickamauga National Military

Park where Confederates routed Union forces in September 1863. Chattanooga sat

as a key gateway to the South. The Confederates won Chickamauga and forced the

Union army to retreat to Chattanooga until reinforcements could arrive. Come they

did up the Tennessee River on steamboats, and at the end of November, General Grant

and his soldiers counterattacked. They dislodged the Confederates from the top

of Lookout Mountain in the Battle Above the Clouds. The next day, Union troops made

a mad dash up Missionary Ridge which sealed a stunning victory and opened up

the Deep South to Sherman’s invasion the next year.

|

| The battlefield at Chickamauga (Photo by Hunner) |

|

| Viewing Chattanooga from Lookout Mountain. In the distance, Missionary Ridge is the low dark line just beyond the city. (Photo by Hunner) |

|

| Atop Missionary Ridge with Lookout Mountain looming in the background. (Photo by Hunner) |

Also at Point Park, I talked with Brad Atkins from

Indianapolis. His family specializes in Civil War parks and again, they have hit

about twice as many of those parks as I have.

Having lunch at the Pickle Barrel back in Chattanooga, I

struck up a conversation with a young man in an NPS ball cap. Patrick worked on

trails at the Grand Canyon last summer and now is doing the same along the

Natchez Trace. His crew goes out for nine days, camping and making trails, and

then they get five days off. This just goes to show that there’s something for

all of us in the parks. I am driven by U.S. history, others by a youthful embrace of our natural beauties, others by the Civil

War, and some to preserve

nature by building trails. Good on all of you who enjoy our parks and historic

sites.

|

| For all those who ever wanted a free shot of Jack Daniels, here it is. (Photo by Hunner) |

I then stopped at the Jack Daniels Distillery in Lynchburg,

Tennessee. Hey, whiskey is history too. As our guide Ron said: “Whiskey greases

the wheels of politics.” Many frontier families supplemented their income by

turning corn into whiskey as did Jack Daniels, who had his own distillery by

the age of 16. In 1866, Daniels was first in line to register his distillery,

making it the oldest such one in the country. I had

an informative, entertaining, and a slightly intoxicating tour of how whiskey

is made.

|

| Tour guide Ron gives us a short lesson on the finer aspects of sipping Tennessee whiskey (Photo by Hunner) |

West of Lynchburg, I jumped onto the Natchez Trace Parkway to

visit the grave of someone I have followed across the country—Meriwether Lewis.

The co-leader of the Corps of Discovery was traveling on the Trace with

the maps and journals from his trip to the Pacific and back when he stopped for

the night at a log cabin. He was found dead the next morning, whether of foul

play or by suicide is unknown.

|

| The memorial over Meriwether Lewis's grave on the Natchez Trace Parkway. (Photo by Hunner) |

I next went to the place where Grant won a reputation for being

a fighting general and won a welcome Union victory in the early part of the

war. In April 1862, the Confederate Army under General Albert Sidney Johnston

and the Union forces under General Ulysses Grant stumbled into each other at

Shiloh Church. Grant wanted to capture the railroad hub of Corinth to the

south. The resulting two-day battle claimed a staggering 3,500 men killed with

another 20,000 wounded or missing. The victory at Shiloh opened up the

Tennessee River for the Union and allowed steamboats coming down the Ohio River

to land its soldiers deeper into the South. It also brought Grant to Lincoln’s

attention who eventually appointed him in charge of the entire U.S. army.

|

| Confederate cannons aimed at the Hornet's Nest at Shiloh. (Photo by Hunner) |

John Wesley Powell, who later had such an influence on the

American West, lost an arm at Shiloh. His biographer, Wallace Stegner,

described it like this: “Losing one’s right arm is a misfortune; to some it

would be a disaster, to others an excuse. It affected Wes Powell’s like about

as much as a stone fallen into a swift stream affects the course of the river. With

a velocity as his, he simply foamed over it.”[1]

Powell led the first expedition down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, rowing with his one arm.

South of Shiloh about thirty miles is Corinth, where the Confederate army retreated to after Shiloh.

South of Shiloh about thirty miles is Corinth, where the Confederate army retreated to after Shiloh.

|

| The crossroads of the Charleston-Memphis Railroad and the Mobile-Ohio Railroad at Corinth, Mississippi. (Photo by Hunner) |

Corinth was like Chattanooga, a hub for railroad transportation into the south. The Confederacy’s

longest east-west railroad line as well as the longest north-south route

crossed here. In May 1862, Union forces attacked and forced the Confederates to

abandon the town. The South tried to recapture it in October 1862 but failed.

Union forces occupied and fortified Corinth until the beginning

of 1864, severing the east and west sections of the South and also cutting the Deep

South from its northern states. Occupied Corinth also attracted "Contrabands,”

slaves who had freed themselves and sought refuge with the Union Army. Eventually,

1,000 ex-slaves from Corinth’s Contraband Camp volunteered to fight in the Civil

War as the 1st Alabama Infantry Regiment of African Descent.

|

| No photos from the Corinth Contraband camp exist but here is what it might have looked like. (From exhibit at the Civil War Interpretive Center, Corinth, Mississippi) |

|

| Two of the 200,000 African American Union soldiers who fought in the Civil War. (From the exhibit at the Civil war Interpretive Center) |

After Corinth, I hooked back east since I wanted to stop by

a couple of possible historic sites in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. I first tried to

find a Tennessee Valley Authority museum near the Wilson Dam. Muscle Shoals was

the first headquarters of the TVA which electrified this region with

hydroelectric power in the 1930s. I had no luck. Then I sought FAME, the music

studio where Aretha Franklin recorded RESPECT and other songs. I did find it,

but being Sunday, it was closed. “C. L. O. S. E. D. —Find out what it means to

me.”

|

| FAME Recording Studio, Muscle Shoals, Alabama. (Photo by Hunner) |

On Monday, I spent the afternoon at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. They built rockets, humongous rockets. I talked with docent Bill Vaughn who worked on the environmental systems which helped humans live in space and reach the moon. With the stages of a massive Saturn V rocket hanging overhead, he broke down how a rocket that weighed 6,000,000 pounds escaped the earth. The first stage lit the candle with 600,000 gallons of fuel which burned in 2 1/2 minutes to produce 7,500,000 pounds of thrust. Having attained escape velocity from the earth, this part of the assembly disconnected and fell into the Atlantic Ocean. The fuel in the second stage burned enough to establish an earth orbit and then that fuel tank was jettisoned over the Indian Ocean. The third stage powered the module towards the moon and then peeled off into the cosmos about halfway there. I had forgotten the simplicity and the complexity of the Moon Shot. Thanks Bill for reminding me about that inspiring time. The Space and Rocket Center also holds Space Camps for students who are driven by science and adventure. I look forward to hearing about some of you getting us back on the moon in ten years.

[1] Wallace

Stegner, Beyond the 100th

Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West, 17.