Sand Creek Massacre

After I visited Bent’s Old Fort, I drove north some seventy

miles to one of the most shocking events of the Indian Wars. In the words of

the NPS, Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site is “profound, symbolic, spiritual,

controversial, a site unlike any other in America.” The exchanges between

Europeans and Native Americans from first contact held both promise and peril.

This unit of the NPS memorializes the peril, where U.S. soldiers savagely attacked

a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho.

This history of the Sand Creek Massacre NHS contains graphic violence. Please don’t read on if this might upset you.

In November 1864, members of the U.S. Army descended on a

peaceful camp of Cheyenne and Arapahoe who displayed from their teepees the

American flag and a white flag of truce. Earlier that year, a different band of

Indians killed Nathan Hungate and his family. When their remains were displayed

in Denver, calls for vengeance rang out. Territorial Governor John Evans issued

a proclamation for “friendly Indian of the Plains” to assemble in safe havens

while authorizing settlers to “kill and destroy… hostile Indians.”[1]

This set the stage for the tragedy that fell on the peoples at Sand Creek who

had nothing to do with the Hungate killings.

|

| Colorado Territorial Gov. John Evans (NPS exhibit panel at Sand Creek) |

Enter Col. John Chivington, hero of the 1862 Civil War

battle at Glorieta near Santa Fe which stopped the Confederate invasion of the West. After the battle, Chivington kept the Glorieta veterans of the 1st Regiment together while adding volunteers into the 3rd Colorado Cavalry. These men,

who missed the victory at Glorieta, had enlisted for only 100 days to fight the

“Indian War of 1864.” According to Park Ranger John Laudnius, the 3rd

Regiment was poorly trained, poorly equipped, and poorly disciplined.

| Col. John Chivington (http://civilwardailygazette.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/march26chivington.jpg) |

Why target this group of Cheyenne and Arapaho who had assembled

in the safe haven of Fort Lyons before setting up at Sand Creek? Many of the U.S.

troops, especially the 3rd Regiment had flocked to the territory of Colorado to

prospect for gold and silver and wanted land occupied by Native peoples.

Additionally, Gov. Evans wanted a transcontinental railroad to pass through

Colorado, which meant going through the land of the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

Total War

To be blunt, European colonists and then the United States has waged total war on Native

Americans for centuries. A year earlier, the army had destroyed crops of the

Navajo in the Four Corners region, attacked them during a winter campaign, and forced them on the Long

Walk to relocate 350 miles away. Total war targets the young, the families, the

elderly to break the support and the will which Indian warriors needed for

their armed resistance. Perhaps that accounts for the blood lust of the U.S. soldiers at Sand Creek.

|

| The Encampment at Sand Creek was near the trees on the right. Soldiers came in from the right and the villagers fled to the creeks bank on the upper left (Photo by Hunner) |

On Nov. 28, 1864, Chivington led 675 men with four

12-pounder howitzers into the encampment along Sand Creek. Away

hunting, few adult male Indians were at the camps of Chiefs Black Kettle, White

Antelope, and Left Hand. At first the women, children, and elderly thought the

thundering hooves meant the return of the long lost bison. George Bent, son of Owl

Woman, a Cheyenne, and William Bent of Bent’s Fort on the Santa Fe Trail (see the May 16 blog) was at the camp: “By the dim light I could see the soldiers, charging

down on the camp from each side… at first the people stood huddled in the

village, but as the soldiers came on they broke and fled.”[2]

The U.S. troops killed indiscriminately as the Native peoples fled northwest

along the creeks banks. Sometimes the soldiers fired at point blank range into

the huddled families.

|

| George Bent and his Cheyenne wife Magpie (http://www.nps.gov/sand/historyculture/images/georgemagpie) |

In total, 165 to 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho died, two thirds

of them women, children, and the elderly. Another 200 suffered wounds. Of the

675 soldiers, sixteen died, some from friendly fire, and seventy were wounded. Thirteen

Cheyenne and one Arapaho chief were killed along with any possibility for

peace. Chief Black Kettle, who survived the attack, continued his call for peace, but Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors retaliated by attacking settlers and

wagon trains in the region. The NPS calls the massacre “8 hours that changed

the Great Plains forever.”

|

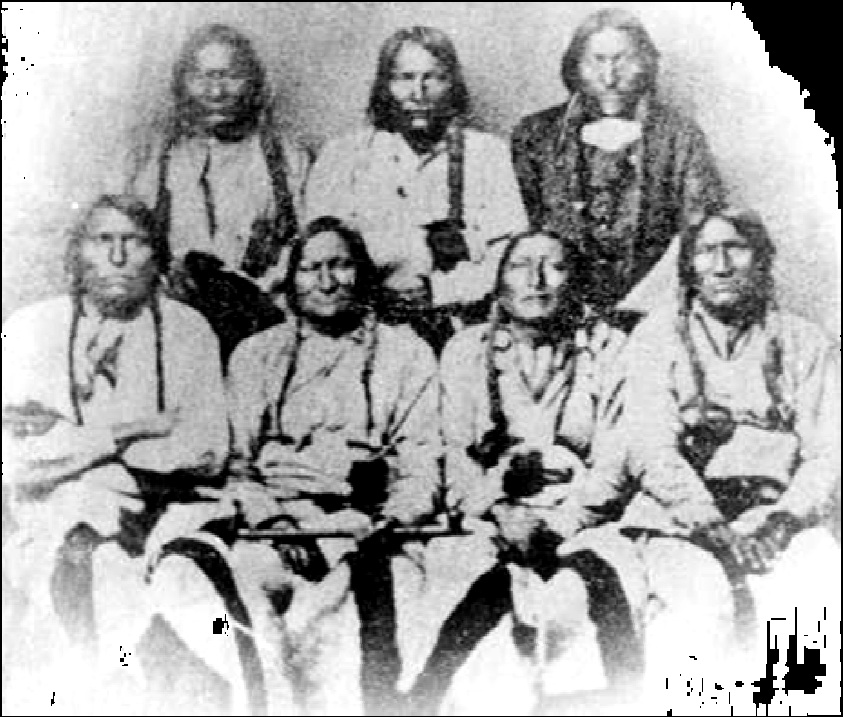

| Chief Black Kettle, holding a pipe in the front row, at a peace conference before Sand Creek (https://www.nps.gov/sand/learn/historyculture/images/Camp-Weld-Conference.jpg) |

Those Who Refused to Fire

Some of the U.S. soldiers disobeyed orders and did not fight. Led by

Captain Silas Soule, who had attended the peace talks earlier that fall, this

company of 100 soldiers refused to participate. Soule wrote an account of the

slaughter: “I refused to fire.and swore that none but a coward would. For by

this time, hundreds of women and children were coming towards us and getting on

their knees for mercy. Anthony shouted,

‘kill the sons of bitches’.” Soule continues with his report. “When the Indians

found that they there was no hope for them they went for the Creek and buried

themselves in the Sand and got under the banks…. By this time there was no

organization among our troops, they were a perfect mob.” As a result, Soule

recalls: “One squaw with her two children were on their knees begging for their

lives of a dozen soldiers, within ten feet of them all, firing – one who

succeeded in hitting the squaw in the thigh, when she took a knife and cut the

throats of her children. and then killed herself.” Soule’s company did not

fire a shot.[3]

|

| Capt. Silas Soule (https://www.nps.gov/sand/learn/historyculture/images/Soule.jpg) |

Some soldiers took body parts as trophies which they paraded

through the streets of Denver. The Cheyenne and Arapaho did not return to the

site nor did the soldiers bury those they killed. In 1868, General William Tecumseh

Sherman toured Sand Creek and found human bones scattered around. He sent them

back to Washington for ballistic analysis on the effectiveness of the weapons

used. These human remains eventually were deposited at the Smithsonian. After

the Native American Graves Protection Act (NAGPRA) passed in 1990, all federal

institutions which held native human remains or sacred objects had to contact

the relevant tribes to repatriate them. At the Sand Creek Massacre NHS, a

Repatriation field on the bluff overlooking the creek bed now holds these

remains along with those body parts chopped from the slain that have been returned

by the descendants of the soldiers.

In the aftermath of the attack, a Congressional Joint

Committee on the Conduct of the War found that Chivington had “surprised and

murdered in cold blood…unsuspecting men, women, and children… who had every

reason to believe that they were under [U.S.] protection.”[4]

Unprovoked attacks, broken treaties, and dispossession of ancestral lands are

perils of contact that our tribes and our country continue to grapple with

today.

|

| The Repatriation Field at Sand Creek (Photo by Hunner) |

When I first arrived at the visitors’ center, a sun burned couple

was asking Ranger John Laudnius questions about the place and the event. John

mentioned that a rifle from that killing field came up for auction, and the NPS

bought it. The park then consulted with tribal elders on what to do with it.

They asked for the park to break it up into small pieces and destroy it. The

woman gasped and said it was a valuable artifact. I replied that it was used to

kill these tribal elders’ ancestors so destroying it made sense to me. The NPS

did not destroy the rifle, but did not exhibit it either.

Native American World Views

I talked with Ranger John about this more. He explained that

native peoples look at and understand the world and history differently than European

Americans. When I pressed him about this, he said: Europeans think of time

linearly. All things happen on a

distinct time line. Native Americans understand time cyclically and so tell

their histories differently. Tribes transmit their histories orally and when a

grandfather tells a story and you retell that story, you tell it as if you are

your grandfather. A further complication with oral tradition emerges since

tribal histories are told in their own languages. When the NPS translated those

Cheyenne and Arapaho stories to English, this filter changed the narratives. From

my interaction with Native Americans in New Mexico, I am continually amazed at

how they perceive and understand the world.

After talking with John, I walked up the hill to the

overlook of the massacre site. It is peaceful today. Crickets chirped along the

trail to the overlook. Whippoorwills sang, an owl hooted from the cottonwoods

that lined the dry creek bed. At the top of the hill with the encampment and massacre

site spread out below, I imagined the chaos and horror as parents frantically

fled or dug shallow holes in the sand to hide their children and themselves.

As I walked back to the visitors’ center, I saw a lone

nighthawk swooping over the cottonwoods. I thought of Sen. Ben Nighthorse

Campbell, a Cheyenne who helped create this park in 2000. For today’s Cheyenne

and Arapaho, this is a place of medicine to heal wounds. The actual creek bed

of the massacre site is off limits to the public. A sign hangs on the overlook

barrier: “Help respect sacred ground. Please stay on this side of the fence.”

|

| The battlefield from the Overlook with signs that say "Help Respect Sacred Ground." (Photo by Hunner) |

We are no stranger to inhumane treatment of our peoples.

Slavery, Indian wars, and Japanese-American internment camps are some of our

biggest failures to live up to the ideals of the Declaration of Independence

and our Constitution. It is a tribute to our country’s self-reflection that we

have units of the NPS which preserve these tragedies. We will visit the battlefields of wars of national destiny and wars of choice, the underground railroads,

the internment camps as well as the successes of our nation. They are important

parts of our nation’s narrative. We will continue to celebrate our successes

and our failures. In doing this, I am just following the lead of our nation's parks.

In 2000, Congress passed, and President Clinton signed the

bill creating the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. It opened to the

public in 2007.